I’ve written several articles in the last few weeks critical of the dangerously unprincipled turn at the Federal Communications Commission toward a quixotic, political agenda. But as I reflect more broadly on the agency’s behavior over the last few years, I find something deeper and even more disturbing is at work. The agency’s unreconstructed view of communications, embedded deep in the Communications Act and codified in every one of hundreds of color changes on the spectrum map, has become dangerously anachronistic.

I’ve written several articles in the last few weeks critical of the dangerously unprincipled turn at the Federal Communications Commission toward a quixotic, political agenda. But as I reflect more broadly on the agency’s behavior over the last few years, I find something deeper and even more disturbing is at work. The agency’s unreconstructed view of communications, embedded deep in the Communications Act and codified in every one of hundreds of color changes on the spectrum map, has become dangerously anachronistic.

The FCC is required by law to see separate communications technologies delivering specific kinds of content over incompatible channels requiring distinct bands of protected spectrum. But that world ceased to exist, and it’s not coming back. It is as if regulators from the Victorian Age were deciding the future of communications in the 21st century. The FCC is moving from rogue to steampunk.

With the unprecedented release of the staff’s draft report on the AT&T/T-Mobile merger, a turning point seems to have been reached. I wrote on CNET (see “FCC: Ready for Reform Yet?”) that the clumsy decision to release the draft report without the Commissioners having reviewed or voted on it, for a deal that had been withdrawn, was at the very least ill-timed, coming in the midst of Congressional debate on reforming the agency. Pending bills in the House and Senate, for example, are especially critical of how the agency has recently handled its reports, records, and merger reviews. And each new draft of a spectrum auction bill expresses increased concern about giving the agency “flexibility” to define conditions and terms for the auctions.

The release of the draft report, which edges the independent agency that much closer to doing the unconstitutional bidding not of Congress but the White House, won’t help the agency convince anyone that it can be trusted with any new powers. Let alone the novel authority to hold voluntary incentive auctions to free up underutilized broadcast spectrum.

What is the Spectrum Screen Really Screening, Anyway?

One particularly disturbing feature of the report was what appears to be a calculated jury-rigging of the spectrum screen, as I wrote in an op-ed for The Hill. (See “FCC Plays Fast and Loose with the Law…Again”) For the first time since introducing the test as a way to simplify merger review, the draft report lowers the amount of spectrum it believes available for mobile use, even as technology continues to make more spectrum usable. The lower total added 82 markets in which the screen would have been triggered, though the staff report in any case never actually performs the analysis of any local market.

The rationale for the adjustment is hidden in a non-public draft of an order on the transfer of Qualcomm’s FLO-TV licenses to AT&T, an order that is only now just circulating among the Commissioners. Indeed, the Qualcomm order was only circulated a day before the T-Mobile report was released to the public and (in unredacted form) to the DoJ.

(Keeping draft documents private is the normal course of business at the agency—the T-Mobile report being the rare and disturbing exception of releasing a report before even the Commissioners have reviewed or voted on it, here in obvious hopes of influencing the Justice Department’s antitrust litigation).

In the draft Qualcomm order, according to a footnote in the draft T-Mobile report, agency staff propose a first-time-ever reduction in the total amount of usable spectrum that forms the basis of the screen. (Under the test, if the total spectrum of the combined entity in a market is less than a third of the usable spectrum, the market is presumed competitive and no analysis is required.)

For purposes of the T-Mobile analysis, the unexplained reduction is assumed to be acceptable to the Commission and applied to calculations of spectrum concentration in each of the local Cellular Market Areas. (The calculation also assumes AT&T has the pending Qualcomm spectrum.) Notably, without the reduction the number of local markets in which the screen would be triggered goes down by a third.

Asked in a press conference today about the curious manipulation, FCC Chairman Genachowski refused to comment.

The spectrum screen, by the way, never made much sense. Its gross oversimplification of total usable spectrum, for one thing, hides a ridiculous assumption that all bands of usable spectrum are equally usable, defying the most basic physics of mobile communications. With a wink to the apples-and-oranges nature of different bands, since 2004 the agency has decided more or less arbitrarily to increase the total amount of “usable” spectrum by including some new bands of usable spectrum and not others, with little rhyme or reason.

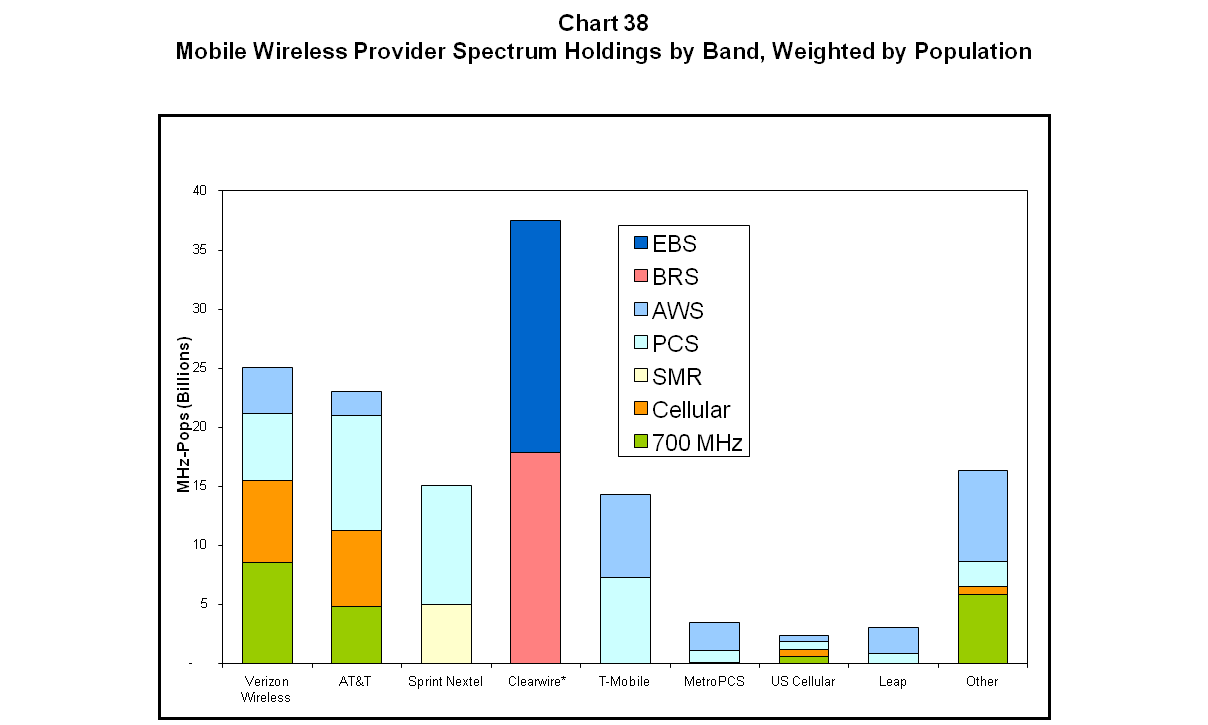

The manipulation of the spectrum screen’s coefficients, in fact, have no rationale other than to fast-track some preferred mergers and create regulatory headaches for others. In truth, a screen that counted all spectrum actually being used for mobile communications, and counted it equally, would suggest that Sprint, in combination with its subsidiary Clearwire, is the only dangerously monopolistic holder of spectrum assets. As Chart 38 of the FCC’s 15th Annual Mobile Competition Report suggests, Sprint and Clearwire hold more “spectrum” than any other carrier—enough to trigger the screen in most if not all CMAs. That is, if it was all counted.

That isn’t necessarily the right outcome either. Much of Clearwire’s spectrum is in the >1 GHz. Bands, and, at least for now, those bands are usable but not as attractive for mobile communications as other, lower bands.

As the Mobile Competition Report notes, “these different technical characteristics provide relative advantages for the deployment of spectrum in different frequency bands under certain circumstances. For instance, there is general consensus that the more favorable propagation characteristics of lower frequency spectrum allow for better coverage across larger geographic areas and inside buildings, while higher frequency spectrum may be well suited for adding capacity.”

So not all spectrum is equal after all. What, then, is the point or usefulness of the screen? And what of this unmentioned judo move in the staff report, which suddenly changed the point of the screen from one that simplified merger review to a conclusive presumption against a finding of “public interest”? The original point of the screen was to quickly eliminate competitive markets that don’t require detailed analysis. In the AT&T/T-Mobile staff report, for the first time, it’s used to reject a proposed transaction if too many market (how many is not indicated) are triggered that would require that analysis.

But why continue to compare apples and oranges for any purpose, when the real data on CMA competition is readily available? The only answer can be that the analysis wouldn’t yield the result that the agency had in mind when it started its review. For in painstaking detail, the 15th Mobile Competition report also demonstrates that adoption is up, usage is off the charts, prices for voice, data, and text continue to plummet, investments in infrastructure continue at a dramatic pace despite the economy, and new source of competitive discipline are proliferating, in the form of device manufacturers, mobile O/S providers, app developers, and inter-modal competitors. For starters.

To conclude that AT&T’s interest in T-Mobile’s spectrum and physical infrastructure—an effort to overcome the failure of the FCC and local regulators to provide alternative spectrum or to allow infrastructure investments to proceed at an even faster pace—isn’t in the public interest requires the staff to ignore every piece of data the same staff, in another part of the space-time contiuum, collected and published. But so long as HHIs and spectrum concentration are manipulated and relied on to foreclose real analysis, it all makes sense.

A Rogue Agency Slips into Steampunk

That is largely the point of Geoff Manne’s detailed critique of the substance of the report posted here at TLF, and of my own ridiculously long post on Forbes. (See “A Strategic Plan for the FCC.”)

The Forbes piece tries to put the staff report into the context of on-going calls for agency reform that were working their way through Congress even before the release. In it, I conclude that the real problem for the agency is that even with the significant changes of the 1996 Communications Act, the agency is still operating in a stovepipe model, where different communications technologies (cable, cellular, wire, satellite, “local”) are still regulated separately, with different bureaus and in many cases different regulations.

The model assumes that audio and video programming are different from data communications, offered by different industries using incompatible, single-purpose technologies. A television is not a phone or a radio or a computer. Broadcast is only for programming, cellular only for voice, satellites only for industrial use. Cable is an inconveniently novel form of pay television, and data communications are only for large corporations with mainframe computers.

Those siloed regulations are further fragmented by attaching special regulatory conditions to individual license transfers and individual bands of spectrum as part of auctions. Dozens of unrelated and seemingly random requirements were added to Comcast-NBC Universal, for example. At the last minute the agency added an eccentric version of the net neutrality rules to the 2008 auction for 700 Mhz. spectrum, but only for the C block.

The agency continues to operate under an anachronistic view that distinct technologies support distinct forms of communications (radio, TV, cable, data). But the world has shifted dramatically under their feet since 1996. The convergence of nearly all networks to the Internet’s single, non-proprietary standard of packet-switching, digital networks operating under TCP/IP protocols has been nothing short of a revolution in communications. But it’s a revolution the agency sat out. It has no idea what role it ought to play in the post-apocalyptic world; nor has Congress given them one.

As different kinds of communications technologies have all (or nearly all) converged on IP, communications applications have blurred beyond the ability to distinguish them. Voice communications are now offered over data networks, data is flowing over the wires, TV is everywhere, and mobile devices that were unimaginable in 1996 now do everything.

Quite simply, the mismatch between the agency’s structure and the reality of a single digital, virtual network treating all content as bits regardless of the technology or the source that transports it has left the agency unable to cope or to regulate rationally. Consider some of the paradoxes the agency has been forced to wrestle with in recent years:

- Is Voice over IP to be regulated as a traditional voice service, with barnacled requirements for Universal Service contribution and 911 services applied and, if so, applied how?

- Is TV on the Internet, delivered using any and every possible technology including wireless, fiber, copper, and cable, subject to the same Victorian standards of decency as broadcast TV, itself now entirely digital?

- Is the public interest served when mobile providers combine spectrum and infrastructure assets, largely to overcome the agency’s own paralysis in moving the deeply fractured spectrum map into even the 20th century and the incompetent and corrupt local zoning agencies that hold up applications for new towers and antennae until the proper tribute is rendered?

In the face of these paradoxes, the FCC has become ungrounded; a victim of its own governing statute, which in many respects requires it to remain anachronistic. Left without clear guidance from Congress on how or whether to regulate what applications (that’s really all we have now—applications, independent of technology), the agency increasingly improvises.

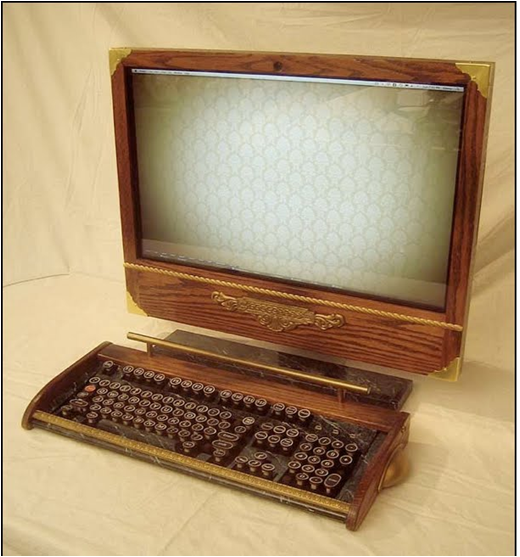

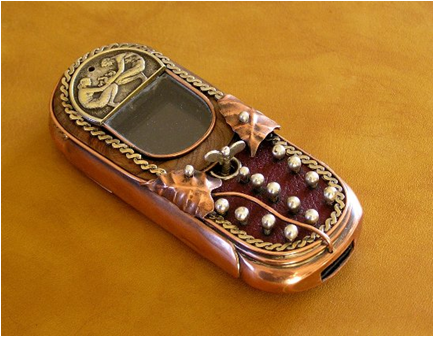

It’s like the wonderful genre of animation known as “steampunk,” where modern technology is projected anachronistically into the past, exploring what life would have been like if the 19th century had robots, flight, information processing, and modern armaments, all powered by the steam engine. (The concept of steam punk has now become a popular design genre, including some functioning devices wrapped in steampunk elements, as in the photo below.)

A Steampunk Computer

It’s cute on film, but applied to the real world it’s simply dangerous. The FCC is required by law to keep its head in the sand with respect both to the realities of digital technology and the economics of the modern communications ecosystem. Yet its natural desire to regulate something leaves the Commission flailing wildly in the dark for a foothold for its ancient regulatory structure in a world it doesn’t inhabit.

The Open Internet Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, for example, asked helplessly in over 80 separate paragraphs for education and update on the nature of the revolution spurred by the deployment of broadband Internet. (“We seek more detailed comment on the technological capabilities available today, as offered for sale and as actually deployed in providers’ networks.”) Of course it had to ask these questions – the agency never regulated broadband. Under the 1996 Act, as the 2005 Brand X case emphasizes, it never could.

Consider just a few of the absurd counterfactuals that the agency’s steampunk policies have led it in just the last few years (more examples greatly appreciated, by the way):

- Broadband isn’t being deployed in a “reasonable and timely fashion” (2011 Section 706 Broadband Report)

- The mobile communications market is not “effectively competitive” (14th and 15th Mobile Competition Report)

- High concentrations of customers and spectrum, calculated using rigged HHIs and spectrum screens, are sufficient to raise presumptive antitrust concerns regardless of actual competitive and consumer welfare (AT&T/T-Mobile draft memo)

- Spectrum suitable for mobile use is decreasing (AT&T/Qualcomm memo)

- Despite a lack of any examples, broadband providers “potentially face at least three types of incentives to reduce the current openness of the Internet” (Open Internet order)

- Encouraging competition and protecting consumer choice “cannot be achieved by preventing only those practices that are demonstrably anticompetitive or harmful to consumers.” (Open Internet order)

- The agency” expect[s] the costs of compliance with our prophylactic rules to be small” (Open Internet order)

- Absent a mandatory data roaming regime for mobile broadband, “there will be a significant risk that fewer consumers would have nationwide access to competitive mobile broadband services….” (Data Roaming order).

Not that there isn’t considerable expertise within the agency, and glimmers of understanding that manage to escape in whiffs from the steam pipes. The 2010 National Broadband Plan, developed with a great deal of both internal and external agency expertise, does an admirable job of describing the current state of the broadband environment in the U.S. More impressive, the later chapters predict with considerable vision the application areas that will drive the next decade of broadband deployment and use, including education, employment, health care and the smart grid.

The NBP, unfortunately, is the exception. More and more of the agency’s reports, orders, and decisions instead bury the expertise, forcing ridiculous conclusions through an implausible lens of nostalgia and distortion. The agency’s statutorily mandated hold on a never-realistic glorious communications past is increasingly threatening the health of the real communications ecosystem–an even more glorious (largely because unregulated) communications present.

I Love it When a Plan Comes Together

The FCC’s steampunk mentality is threatening to wreak havoc on the natural evolution of the Internet revolution. It’s also turning the FCC from a respected and Constitutionally-required “independent” agency that answers to Congress and not the White House into a partisan monster, pursuing an agenda that’s light on facts and heavy on the politics of the administration and favored participants in the Internet ecosystem. The agency relies on clichés and unexamined mantras rather than data—even its own data. Mergers are bad, edge providers are good, and the agency doesn’t acknowledge that many of the genuine market failures that do exist are creatures of its own stovepipes.

As I note in the long Forbes piece, there was a simple, elegant way to avoid the steampunk phenomenon –an alternative that would have saved the FCC from increased obsolescence and the rest of us from its increasingly bizarre and disruptive regulatory behavior. And in came from within the walls of FCC headquarters.

In 1999, in the midst of the first great Web boom, then-chairman William Kennard (a Democratic appointee) had a vision for the future of communications that has proven to be entirely accurate. Kennard created a short, straightforward “strategic plan” for the agency that emphasized breaking down the silos. It also took a realistic view of the agency’s need and ability to regulate an IP world, encouraging future Chairmen to get out of the way of a revolution that would provide far more benefit to consumers if left to police itself than with an FCC trying to play constant catch-up.

Kennard also proposed dramatic reform of spectrum policy, recognizing as is now obvious that imprinting the agency’s stovepiped model for communications like a tattoo on the radio waves was unnecessarily limiting the uses and usefulness of mobile technology, creating artificial scarcity and, eventually, a crisis.

In just a few pages of the report, the strategic plan lays out an alternative, including flexible allocations that wouldn’t require FCC permission to change uses, market-based mechanisms to ensure allocations moved easily to better and higher uses (no lingering conditions), even the creation of a spectrum inventory (still waiting). The plan called for incentive systems for spectrum reallocation, an interoperable public safety network, and expanded use of unlicensed spectrum. All reforms that we’re still violently agreeing need to be made.

We’ve arrived, unfortunately, at precisely the future Kennard hoped to avoid. And we’re still moving, at accelerating speeds, in precisely the wrong direction. Instead of working to ease spectrum restrictions and leave the “ecosystem” (the FCC’s own term) to otherwise police itself, recent NPRMs and NOIs suggest an agency determined to leverage its limited broadband authority into as many aspects of the converged world as possible. As the Free State Foundation’s Seth Cooper recently wrote, today’s FCC has developed a “proclivity to import legacy regulations into today’s IP world when doing so makes little or no sense.”

Fun’s fun. I like my steampunk as well as anybody. But I’d prefer to see it on a mobile broadband device, or over Netflix streamed through my IP-enabled television or game console. Or anywhere else other than at the FCC.