Over the weekend, I published an op-ed in The Des Moines Register encouraging the FCC to heed the lessons of the first national broadband plan, the one Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin sent to Congress in 1808.

Over the weekend, I published an op-ed in The Des Moines Register encouraging the FCC to heed the lessons of the first national broadband plan, the one Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin sent to Congress in 1808.

Gallatin was a remarkable figure in the early history of the federal government, and his accomplishments include being the longest-serving Treasury secretary (1801-1812) to date. His report on the Subject of Public Roads and Canals, completed at the request of Congress, remains one of the seminal documents in the history of American infrastructure. It is a masterpiece of dispassionate policy-making and clear-headed writing.

Alas, the document is available nowhere online, and the only in-print copy I can find is published by the aptly-named Dodo Press. This is indeed unfortunate given the renewed interest in network infrastructure as a form of national technology. The NBP published in March by the FCC, despite its nearly 400 pages and thousands of footnotes, makes no reference to Gallatin or his plan.

Two hundred years ago, Gallatin’s proposal was audacious. The young Republic, in danger of coming apart at the seams of its already-diverse geography, should commit to building a series of road and canals to knit the continent together from the Atlantic to the Mississippi. The Gallatin Plan called for canals that would connect the inland waterways of the U.S. from Massachusetts to North Carolina, a “great turnpike road from Maine to Georgia,” and improvements, including what would one day become the Erie Canal, to connect the waterways of the Atlantic with the Great Lakes.

The value of roads and canals in improving the communications, safety, and commerce of the young republic were too obvious to enumerate. Indeed, Gallatin wrote, “No other single operation, within the power of the government, can more effectually tend to strengthen and perpetuate that union, which secures external independence, domestic peace, and internal liberty.”

Gallatin estimated his proposed new infrastructure would cost the federal government $20 million. In countries with a “compact population,” he noted, such expenditures might be expected to come from “individual exertion, without any direct aid from the government.” But the vast geography of the United States, its sparse population, and the general poverty of many of its citizens, justified public investment. As the federal government was already in debt, Gallatin advised Congress to borrow the money from future budget surpluses in $2 million increments over a ten-year period. (The surpluses were expected to come from the sale of western lands.)

President Jefferson, elected on a platform of limited federal government, balked at the scale of Gallatin’s ambition, and rejected outright the then-novel idea of borrowing ahead of tax revenues. Gallatin’s plan was kicked around Congress until the War of 1812 reversed Gallatin’s painstaking efforts to retire the federal debt and ended any hopes of massive civilian projects. Construction of the Erie Canal started in 1817; the canal opened in 1825. Like the other projects called for in Gallatin’s plan, it was financed with a combination of state and private money.

The Uniquely American Approach to Infrastructure

Gallatin’s plan may have been the first to call for new national infrastructure, but in both its ambitions and its eventual execution it finds many parallels with other great American infrastructures. These include the construction of the transcontinental railroads, the banking system, electricification, civil aviation, commercial radio, and the build-out of the telephone and telegraph networks.

Those interested in the still-controversial realities as opposed to the myths of how these networks were built are encouraged to read the remarkable series of monographs written by Dr. Amy Friedlander and published by Robert E. Kahn’s Corporation for National Research Initiatives. See http://www.cnri.reston.va.us/.

In short, all U.S. infrastructures inevitably require complicated and delicate private-public partnerships. Private capital, motivated by the hopes of profit, provides the bulk of the investment and absorbs the bulk of the risks. Federal and often local governments provide support in the form of land grants, rights of way, investments in basic research for key technologies, encouraging standards, and financial markets that created liquidity for instruments necessary to finance construction.

(The interstate highway system followed a different model, largely funded by the federal government. The justification—at least officially–for this massive federal program was national defense; the system was built at the height of the Cold War. In that sense, it looks more like a military expenditure than an investment in infrastructure.)

Financing is essential, for infrastructure is characterized by heavy initial investments relative to on-going operating costs once construction is complete. The risk of failure is very real. If you build it and they come, to paraphrase “Field of Dreams,” the network can provide solid profits for generations. If they don’t come, you lose everything. Timing also matters. Traffic may arrive later than you think, by which time you had sold out your investment at bargain-basement or bankruptcy rates, only to watch others ultimately profit from your vision. (See, for example, “Man, Plan, Canal”)

In some cases governments provide outright subsidies for populations or geographies for whom the cost of providing service clearly exceeds any hope of profit under a traditional capitalist model.

Serving these communities is important not merely for egalitarian reasons, however, but because of the increasing returns to scale that network technologies offer. The more people who are connected to a network, the faster its value to all participants increases. Many of those who cannot afford access, according to network theory, will contribute value beyond the cost of providing it to them for free or at a price below cost.

First in Adoption, Fifteenth in Per Capita

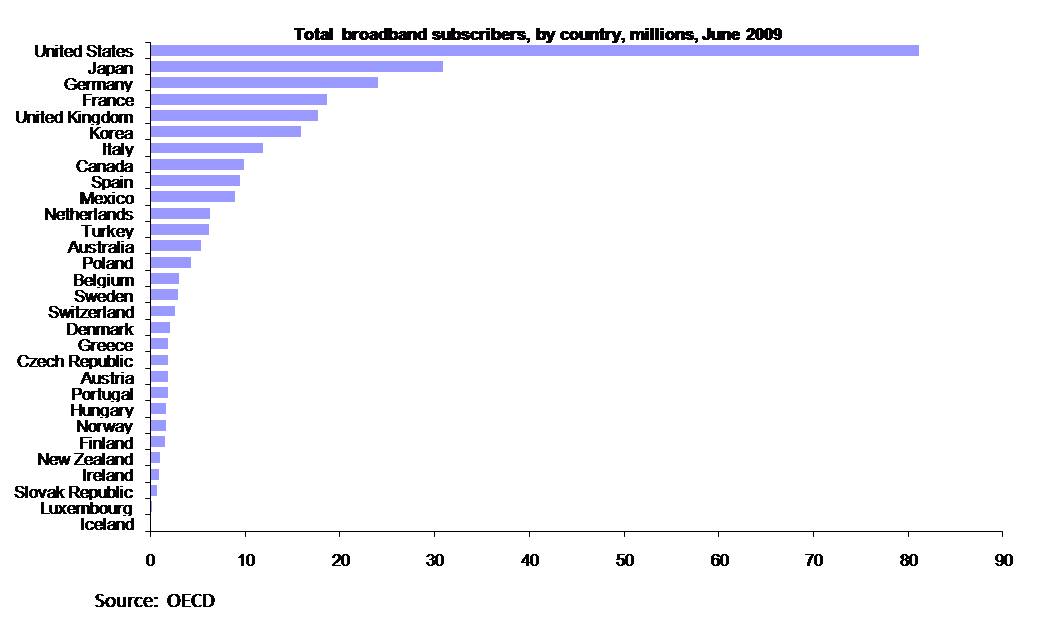

This uniquely American model of infrastructure development and deployment, by the way, undermines one of the principal arguments for increased federal involvement in broadband Internet–the low percentage of broadband penetration in the U.S. relative to some countries in Asia and Western Europe. The most recent data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) shows that the U.S. as of June 2009 had by far the largest number of broadband Internet users at 81 million (Japan, #2, has only 31 million.) But as a percentage of population, the U.S. ranks #15.

It is that latter number that has been the focus of those, including the authors of the NBP, who argue that the U.S. is lagging far behind other countries in the adoption of broadband. But that comparison fails to take into account several uniquely American factors, including the extreme geography and low population density of much of the U.S., as well as the diversity of its population in economic and cultural characteristics.

It is that latter number that has been the focus of those, including the authors of the NBP, who argue that the U.S. is lagging far behind other countries in the adoption of broadband. But that comparison fails to take into account several uniquely American factors, including the extreme geography and low population density of much of the U.S., as well as the diversity of its population in economic and cultural characteristics.

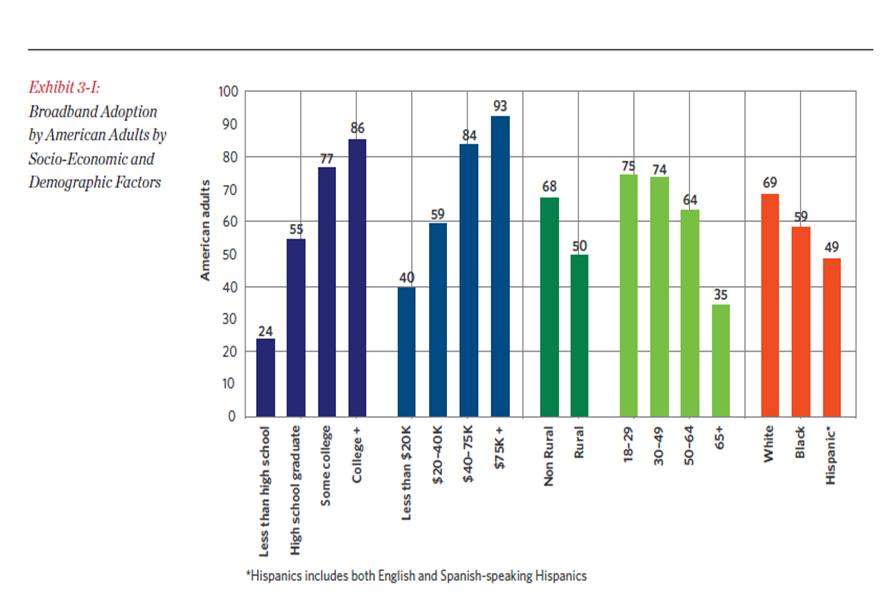

As the NBP notes, for example, 95% of Americans have access to broadband already (more if you count mobile broadband). But only two-thirds of the population have actually signed up for broadband service, with significant lags among Americans based on education, income, and age. 86% of college graduates have broadband; only 24% of those with less than a high school education. Only 35% of Americans over 65 have adopted broadband.

So the reality is that the U.S. lags not in investment or availability but in adoption. Adoption, in turn, is highly correlated with income, education and age. Reaching these populations and providing them with the proper incentives to adopt —including education as to the value of Internet access as well as, where necessary, subsidies to help pay for access–should be the focus of the FCC’s implementation of the NBP.

So the reality is that the U.S. lags not in investment or availability but in adoption. Adoption, in turn, is highly correlated with income, education and age. Reaching these populations and providing them with the proper incentives to adopt —including education as to the value of Internet access as well as, where necessary, subsidies to help pay for access–should be the focus of the FCC’s implementation of the NBP.

When Regulation Matters

Blaming the lower per capita adoption—and using it to justify regulatory intervention—on the supposed failure of ISP competition, the absence of enforceable net neutrality rules, and the lack of meaningful FCC supervision of ISP business practices under Title I of the Communications Act are all red herrings. They ignore the historical lessons of Gallatin’s plan and the infrastructures that have been successfully deployed since then. Worse, they are leading the FCC down a rabbit hole of unnecessary regulation that is likely to do more harm than good.

More of that in a moment. But I don’t want to suggest that regulation is never an important component in the on-going management of infrastructure. Though the general theory of “natural” monopoly for infrastructures has been largely discredited, the fact remains that infrastructure providers may achieve limited monopolies based on local geographies or particular applications—long distance interconnection in the case of the early success of AT&T or web-based search in the case of Google today.

Depending on switching costs and the costs of new entrants (often with cheaper technology with better performance), such monopolies can last a long or short time. Such monopolies may prove valuable to consumers and require no interventions to correct. In other cases, most consumers may benefit from the monopoly while specific groups are significantly harmed. Here the case for intervention is stronger.

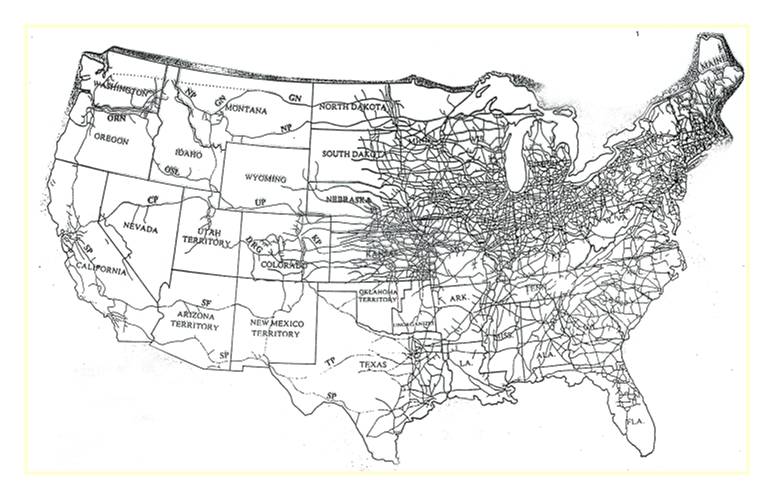

But the cost and risks of that intervention is itself a factor in deciding whether or how to regulate. Success is not always guaranteed. A map of the U.S. rail system in 1900 makes clear that despite intense (indeed, excessive) competition for traffic east of the Mississippi as well as multiple roads crossing the mountains to the west coast, some communities in the inter-mountain region had only one choice of carrier.

But the cost and risks of that intervention is itself a factor in deciding whether or how to regulate. Success is not always guaranteed. A map of the U.S. rail system in 1900 makes clear that despite intense (indeed, excessive) competition for traffic east of the Mississippi as well as multiple roads crossing the mountains to the west coast, some communities in the inter-mountain region had only one choice of carrier.

Those carriers often tried to recover their losses elsewhere by squeezing captive markets, putting real economic strain on inter-mountain communities. Powerful political movements, including the Progressives and the Graingers, rose in response. They claimed, not without cause, that the railroads had effectively been given sovereign powers and were exercising them in tyrannical fashion.

The Congress of Theodore Roosevelt, worried at the very real prospect of violent insurrection, responded by requiring railroads to offer just and reasonable rates to all shippers. Toward that end, Congress in 1906 passed the Hepburn Act, which gave the ICC authority to set maximum rates of carriage for individual commodities. In 1910, the Mann-Elkins Act overturned a court decision that limited the ICC’s ability to deal in particular with the practice of charging inter-mountain shippers rates that built in the cost of backhauling cargo to the coasts even when freight moved directly.

The results, it is fair to say, were catastrophic. Determining reasonable rates, for starters, required the ICC to first determine a reasonable rate of return on investment in the railroad infrastructure, and after ten years of effort the Bureau of Valuation simply gave up, unable to determine, for example, the value of the land grants and rights of way. (The land was worthless without the railroads, valuable with them. What basis should apply?)

A special federal appellate court, the Commerce Court, created to review ICC orders was disbanded after three years amid charges of corruption. U.S. railroads sunk into a morass of regulation and proved unable to compete with new modes and new technologies. Today, the most frequent activity for federal courts reviewing railroad matters is to review applications to abandon routes, which requires government permission.

Lessons Learned and Otherwise

This is no mere review of history. There are important lessons in the story of earlier infrastructures that will determine whether or not the implementation of the NBP succeeds or fails. History also offers important warnings the FCC would do well to heed as it pursues a parallel efforts to appoint itself enforcer of the neutrality principles that have presided without significant government involvement since broadband was invented in the mid-1990’s.

Back to the current NBP. The Internet is unique in many ways, but in particular in that it is both a transportation and a communications infrastructure. In that sense, it has remarkable potential to continue Gallatin’s plan to knit together the different populations of the American continent not only commercially but as citizens. We use broadband technology today not only for commerce but for entertainment, interpersonal communications, political action, public safety, education, energy management, and health care.

The NBP recognizes each of these different uses and does an admirable job laying out the case for expanding broadband technologies and adoption to advance important national goals for each. “Like electricity a century ago,” to quote the plan, “broadband is a foundation for economic growth, job creation, global competitiveness and a better way of life.”

What is curiously absent from the plan’s heft, however, is any indication of the cost of achieving its ambitious goal of 100 mbps access for 100 million Americans by 2020. Or, for that matter, who is expected to pay that cost. FCC estimates have placed the number at $350 billion. Implicit in the plan, of course, is the assumption that the vast majority of that amount will come not from taxpayers but from investors—that is, from shareholders of the cable, telephone, satellite and wireless industries.

That assumption is no surprise. Americans have proven stubbornly Jeffersonian when it comes to infrastructure investments; other than the interstate highway system, no Gallatin has stepped forward since 1808 to recommend full or even significant direct funding for new networks.

And, happily, the broadband industries like the infrastructure entrepreneurs who preceded them, have demonstrated a long-standing willingness to make the necessary investments. This has been true even during times of economic weakness and despite the not-insubstantial risks of loss that come with massive build-outs. Broadband technology deployments have continued through the aftermath of the Internet and telecom bubble in 2000, the recession that followed 9/11, and the most recent economic catastrophes with the bursting of the housing bubble and banking industry in 2008.

Thus there is every indication that the authors of the NBP have heeded, albeit implicitly, one of the key lessons of earlier infrastructure deployments. And that is to rely principally on private funding even in cases where centralized planning and deployment may be the more efficient and democratic mechanism for connecting all populations.

The FCC’s Regulatory Schizophrenia

Which is what makes the FCC’s regulatory schizophrenia so baffling. On the one hand, we have the vision and inclusiveness of the NBP. The plan sets important stretch goals for access providers and as well as application developers. It establishes important roles for the Commission in supporting industry efforts and stepping in where needed to encourage adoption by unwired communities.

On the other hand, we have the heavy-handed efforts to push the net neutrality rulemaking along with last week’s announcement that to solve the minor problem of a complete lack of Congressional authorization, the agency will undertake the legally-dubious process of giving itself the power to oversee broadband under Title II common carrier regulations.

Those rules increasingly make no sense for the technology they were written to deal with–wireline phone service or POTS. Indeed, the lesson of the years since the 1996 Communications Act should be that Title II destroys value and diminishes service for nearly everyone, much as the ICC’s “just and reasonable” ratemaking did to the railroad industry—once the pride of American technology.

Instead, however, the FCC now plans to bring broadband under at least some of the legacy regulations of Title II. Why? The handful of isolated incidents where network management activities have inconvenienced some broadband users (some if not many of whom, in the Comcast case, were engaged in illegally downloading copyright-protected content using the BitTorrent protocol) hardly rises to the level of discrimination that justified the Hepburn and Mann-Elkins Acts. A few self-appointed public advocates, with broader agendas for nationalizing the media and communications industries, do not a Progressive or Grainger movement make.

And even if the problem were real and not academic, the likelihood that the FCC could solve it without disastrous unintended consequences is very low. This is no criticism of the agency, but a reality of the poor fit between fast-changing network infrastructures and the slow pace of regulatory process.

The FCC would do well to study the successes and failures of previous efforts to solve discriminatory network practices. In the case of the ICC, most railroad historians and economists agree that the implementation of corrective efforts–efforts the ICC would never have thought to undertaken without clear guidance from Congress–did far more damage to all shippers. Those who were the intended beneficiaries of the law were, ironically, the worst victims of the unintended consequences of implementation.

The ICC was captured by the industry it regulated, which used rate-setting to reduce competition and stabilize prices (much as the airlines used the Civil Aviation Board). Management grew unable to respond to real competition when it emerged, leaving the inter-mountain region hardest hit when contraction began.

If nothing else, the dogged and increasingly desperate pursuit of regulatory authority over broadband practices will diminish if not poison the investment climate for precisely the kinds of high-risk expenditures necessary to achieve the NBP’s goals. Already, Wall Street has responded to the FCC’s proposed land-grab by downgrading the stocks of publically-traded ISPs. That comes as a surprise only to consumer advocates who, presumably, have never managed a public company of any size.

As George Santayana wrote, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

As George Santayana wrote, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

In this case, unfortunately, even those who remember the past may be victimized along with everyone else by high-minded but wrong-headed efforts to protect consumers from a harm that doesn’t exist with little consideration of the potential cost of doing so.

Where is the dispassionate thinking of a new generation of Albert Gallatins when we need them most?