I’m pleased to be one of the initial signatories of the Center for Democracy and Technology’s Call to Defense and Celebration of the Online Commonwealth. The document, drafted by Cyberspace law pioneer David R. Johnson, nicely balances the remarkable success of online self-regulation with the need for innovative solutions to new problems posed by new kinds of interactions made possible by continued advances in technology. Please consider signing the document.

Monthly Archives: September 2009

Praise for David Post's "In Search of Jefferson's Moose"

Just as I was finishing the manuscript for “The Laws of Disruption,” my old friend David Post published “In Search of Jefferson’s Moose ” a wonderful monograph on, as he says, the state of cyberspace.

Just as I was finishing the manuscript for “The Laws of Disruption,” my old friend David Post published “In Search of Jefferson’s Moose ” a wonderful monograph on, as he says, the state of cyberspace.

Unlike many law professors who write books about Internet technology, Post is no dilettante. He has a deep understanding of the engineering underlying the basic network protocols, and weaves that knowledge into an extended historical metaphor of the founding principles of the American Republic, particularly of the philosophy of government embraced and expanded by Thomas Jefferson.

Post ‘s section on Internet governance wisely stays out of the weeds and sticks with the most important high-level decisionmaking–how new protocols are propagated, how domain addresses are maintained, whether digital life is “governable” by traditional legal institutions. I share his view that cyberspace is not simply a new technology that can be regulated as well or as poorly as previous technologies. Rather, it is a new frontier and, like earlier frontiers, is one that is and will develop its own approach to governance.

It’s a fast read, and well worth the time.

Update on Google Books Settlement – Strange Bedfellows

![]() The deadline for filing objections to Google’s settlement with the Author’s Guild and the Association of American Publishers has now past. Miguel Helft summarizes some of the last-minute objections in an article in yesterday’s New York Times.

The deadline for filing objections to Google’s settlement with the Author’s Guild and the Association of American Publishers has now past. Miguel Helft summarizes some of the last-minute objections in an article in yesterday’s New York Times.

I explained some of these arguments in an earlier post. What is interesting to note about the last-minute filings (including one from longtime Silicon Valley antitrust lawyer Gary Reback) is that they suggest not so much a coalition of opponents as a wide range of people with an axe to bear against the settlement, most with very different agendas for doing so.

The concern that the settlement gives Google a de facto monopoly on digital copying for out-of-print books seems strained for two reasons. Right now, there are of course NO publishers making those books available in any medium. Second, there’s nothing in the settlement that precludes any other entity from making a similar arrangement. If it is a monopoly, in other words, it’s only because no one is trying to compete.

Once More into the Tar Pits of Privacy Policy

No doubt the gooiest problem at the intersection of technology and law continues to be what is unhelpfully referred to as “privacy.” I’ve clipped five articles in just the last week on the subject, including several about Facebook’s efforts to appease users and government regulators in Canada, demands by Switzerland to Google to stop its “street view” application, and a report from Information Week about proposals from a coalition of U.S. public interest groups for new legislation to beef up U.S. privacy law.

The term “privacy” is unhelpful because, as I explain in Chapter 3 of “The Laws of Disruption,” it is a very broad term applied to a wide range of problems. “Privacy” is shorthand for problems including government surveillance, criminal misuse of information, concealment of personal information from friends and family, and protection of potentially harmful or embarrassing information from employers and other private parties (e.g., insurance firms) who might use it to change the terms of business interactions (e.g., increasing premiums when your vehicle’s RFID toll tag tracks your tendency to speed.)

Unfortunately, all of these problems are included in discussions about privacy, and in many cases it’s clear the different parties in the conversation are actually talking about very different aspects of the problem.

Beyond the definitional issues, there is also what one might think of as the irrational or emotional side of privacy. Instinctively, and for different cultural reasons, most of us have a strong reaction to new products and services that will make use of what we think of as intimate facts about ourselves and our activities, even when the goal of that use is to improve the usefulness of such products or make them available at a lower cost.

In the U.S., the national character of the “frontier” nation stressed the desire of eccentric individuals to get away from the moral, religious, or social strictures of European life.

In Europe, historical events in which private information was abused to horrific ends (the Inquisition, the Holocaust, the oppression of life in the Soviet Union and its satellites such as East Germany, where as many as one in three citizens were paid informants on the others) bubble just below the surface of the “debate” about “privacy.”

At one extreme, a small but vocal group of pseudo-millenialists believe that identification technologies are a signal of the coming of the Antichrist, as prophesized in the Book of Revelations.

Of course the problems faced by policy makers on a day-to-day basis seem modest, even trivial, in isolation. Users of Facebook applications (quizzes and the like) allow outside software developers to use the identity of their friends to pass scores around, or to challenge other users. Google Street View, which aims to enhance Google Maps with real photos of streets and houses, inadvertently and perhaps unavoidably take photos that show random but identifiable people and vehicles that happened to be present when the photos are taken.

Behavioral advertising aims to take contextual information about what users are doing online to present ads that are more likely to be of interest than the kind of random guessing that has historically been the realm of ads, such as those that might show up during a television program.

I have to be honest and say I too have a visceral reaction when a targeted ad pops up in an unexpected context, as happens regularly on Facebook, Google, and other applications where I might be engaged in a variety of personal and business communications.

It always reminds me of the time, in the early 1980’s, when I called in to a local cable access program in New York where a hippie astrologer gave consultations on the air, aided by a small, well-dressed man sitting next to her with a laptop computer. There was no tape delay on the show, and when I was on the air, the TV was literally talking directly to me, a true out-of-body experience. (The astrologer also gave profoundly good advice!)

Like most consumers, however, I quickly get over that response and realize that the appearance of intimacy, indeed of inappropriate intimacy, is just that—an appearance. Google isn’t trying to get photos of people who aren’t where they’re supposed to be. Facebook isn’t trying to undermine my personal relationships.

Behavioral ads appear to be personal, but the reality of course is that ALL of the processing is being done by cold, lifeless, uncaring computers. Gmail may “read” the contents of my messages in order to serve me certain ads. But Gmail is not a person, and there is no person or army of persons at Google sitting around reading my mail. No one, sad to say, would care enough to do so. I’m not worth blackmailing. And blackmailing is already a crime.

National governments and public interest groups can and will continue to impose new conditions on Internet products and services (Europeans, for example under Directive 95/46 have a powerful right against any use of their personally-identifiable information.)

The reality, however, is that such regulations are always straining for a balance between the visceral response to “new” privacy invasions and the benefits to consumers that comes from allowing the information to be used. That, in the case of business use of information, is always the goal, even if it’s consumers as a whole who benefit rather than the individual, as in my driving habits/insurance example. (Companies make lots of mistakes, and launch ill-conceived products and services, and some of the abuses have been spectacular and public. Criminal use, such as identity theft, and government surveillance, again, are different problems.)

For the most part, consumers, if only unconsciously, seem to know how to weight the pluses and minuses of new uses of “private” information and decide which ones to allow. I don’t mean to suggest that the market is always right, and never needs external correction. But for every change in privacy law that requires new disclosures, opt-in or opt-out provisions, and other consumer protection, it doesn’t seem to take long for most if not the vast majority of consumers to agree to let the information flow where it may. Information, even private information, wants to be free.

Much Ado About Google Books Proposed Settlement

As L. Gordon Crovitz of The Wall Street Journal points out in his August 17th, 2009 column, 60% of all books are out-of-print but still protected by copyright. Yet Google’s effort to make these books available through cheap digital copies is being met with fierce opposition from an unlikely coalition of publishers, libraries, European governments (who seem to oppose everything these days), law professors, and, just recently, Amazon.com.

This is a complicated story, and a variant of the “it all goes back to” problem. Whether Google’s efforts are to be seen as a public service or a massive land grab, whether the settlement does or does not make sense, depends on how far back you go in unraveling the problem.

First a little background. Google, in its typical audacious way, simply started its project to digitize some of the world’s largest libraries. Eventually that effort caught up with the sleeping drones at the Association of American Publishers and the Author’s Guild, who sued the company in 2005, claiming that regardless of how or even whether these digital copies were made available for use, Google was committing copyright infringement on a massive scale.

Google claimed its activities were protected by the much-abused doctrine of “fair use,” but in 2008 the company reached a tentative settlement with the plaintiffs. Under the pending agreement, participating publishers and authors would receive royalties from any revenue Google derives from the effort, in exchange for immunizing Google against any further copyright infringement claims. Under the settlement, copyright owners (whether publisher or authors) who do not wish to participate in the settlement must affirmatively opt-out. (See the Google Settlement FAQ here.)

The principal objection to the settlement is that it gives Google too much power, effectively granting a monopoly for digital books, especially those that are out of print and whose ownership is unknown (so-called “orphan” works). Such books will be included in the settlement because the owners of their copyrights can’t, by definition, opt out. Perhaps other on-line publishers will be granted similar rights in the future, but until then, Google will be the sole producer of copies. For now, of course, there are no producers of copies, and, given the unknown ownership status of these works, how could there ever be producers of copies until the copyrights on these works expires?

How can books become orphans in the first place? The answer is the one-size-fits-all nature of copyright protection, which extends monopoly power to the author of a work (or a publisher to whom she assigns that power) from the moment of creation until 70 years after the author’s death. For published books that never earned a profit (most books fall into this category, by the way), it is often the case that ownership interests languish. Publishers are unlikely to keep records of such books for 100 years or so, and authors are unlikely to dispose of their rights in their wills. Interests may be subdivided to the point of being untraceable.

So the real problem goes back to copyright, or in this case to its extremely generous duration. In the U.S., copyright protection started out much more modestly, lasting only 14 years. Most of the extensions have taken place in the last fifty years, under pressure from large media companies who hold vast hordes of copyrights that continue to generate profits.

Prof. Lessig has argued that a simple solution to the orphan problem is to require copyright holders to register their rights with the Copyright Office, and to reassert their interests periodically (say, every five years) if they still want protection. Once an author fails to re-register, the works falls into the public domain, and anyone can do whatever they want with it, including producing and selling (but not copyrighting) new copies.

Indeed, registration was required under the Copyright law until 1976. Given the explosion of new content made possible by cheap publishing technology, it was felt at the time that registration and other technical requirements would hold back the development of valuable information and impose unnecessary costs and bureaucracy on a system that would work just fine on its own. Thanks to the Law of Disruption, of course, the cost of producing, publishing and distributing information has only fallen, at an accelerated rate.

Still, the same technology could be used to create a low-cost registration system. But in reality, only popular works would be registered, and everything else would fall into the public domain. Lessig’s proposal is an elegant, clever solution to a serious problem that goes well beyond orphan works. Which is to say it would undo, for the most part, the excessive extensions of copyright granted at the urging of large media companies.

Or rather, it would effectively create a two-tiered system of copyright. Popular works would continue to be registered, and would continue to get excessive protection (life plus 70 years). Unpopular works would fall into the public domain in a matter of a few years.

Well, that’s a start. But the real problem is excessive protection. The solution to that problem is to go back to the drawing board, and create a copyright system that grants only so much protection as is needed to incentivize information production without stifling the free flow of information for a century or so. Popular works do not need 100 years or more of protection. The land grab has already happened, and keeps happening every time Disney finds itself coming close to losing control of a single shred of its content.

The real fix would require us to look well past the Google settlement, past the moribund fair use doctrine, past the orphan works problem, and straight into the abyss.

The Disruptive Power of Digital Life

A new report just out from Forrester confirms my long-standing view that the migration of American households to a digital life is accelerating, the leading side-effect of the Law of Disruption.

A summary of the report in The New York Times on Sept. 2, 2009 notes that the speed with which consumers are adopting disruptive technologies is increasing. Where earlier disruptive technologies such as railroads and telephones took decades to achieve mainstream status, digital technologies follow a much shorter cycle–getting shorter still all the time.

According to Charles S. Golvin, co-author of the report, “The digitization of our daily lives has been steadily ramping up over the past decade.” For example, HDTV will reach 70% penetration within five years. Sixty-three percent already have broadband access.

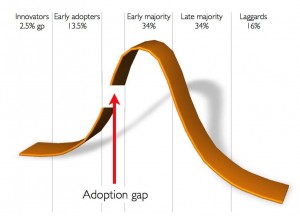

Most technology followers are familiar with the technology adoption curve shown below.

The curve suggests that the majority of consumers wait until innovators and early adopters have already embraced new technologies, working out the bugs and building up enough base to drive prices down. In Geoffrey Moore’s famous adaptation of the curve, technology marketing requires an early focus on the gadget geeks, but requires a critical shift to the later-stage adopters at just the right moment, or what Moore referred to as “the chasm.”

The Forrester report does not challenge the shape of the curve, only the timeframe with which digital technologies move through it.

As I argue in “The Laws of Disruption,” the increase in speed causes increased conflict with social, economic and legal systems that adapt much more slowly to change than do today’s consumers.

As a simple but representative example, consider a story from CNET’s Stephen Shankland on the same day. Photo hosting service Flickr announced a change in its policy for handling claims of copyright infringement, based on outrage over the removal of parody images of President Obama photoshopped to look like the Joker from “Batman: The Dark Knight.” Where the company used to simply remove an image whenever it received a notification that it violated copyright, the company announced it will now temporarily replace the image but allow comments about it to remain in place pending investigation.

According to CNET, none of the likely owners of relevant copyrights (the original photo, DC comics, etc.) had complained about the Obama photo. But under the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act, Internet hosts that do not respond to notices (even those that may be overbroad or outright fakes) risk losing their immunity for what can be very expensive damages. As digital images can flow freely and any home computer user can make modifications to them, keeping up with copyright’s outdated sense of “ownership” becomes a razor’s edge for companies like Flickr.